We live in dark times, and it’s feeling stranger and stranger to write this blog without acknowledging that. As someone other than me has already said, whatever you think the German people should’ve done in the 1930s, this is the time to do it. We can’t all be heroes but we can be honorable people. Sometimes that alone is heroic. Do what whatever is in your power, my friends. We can’t know how long the chance will last.

The hedgehog in British culture

If you grew up on the Beatrix Potter books, you’ll have the hedgehog firmly implanted in your mind as a much-loved part of British culture.

How do I know that? I don’t, but if you say something authoritatively enough and if it’s not too improbable, you can generally get away with it.

In fact, these days, even if it’s outright impossible but you’re leading a political party–

Yeah. It’s pretty grim out there. Don’t forget to demonstrate, write to any government representative you can, and vote first chance you get. To the extent that it’s safe, talk to your friends and neighbors about what’s happening in the world, because that’s part of the national conversation and you can’t know in advance what will make a difference. Within the limits of sanity, do whatever else you can think of. Short of assassination and its friends and relatives, of course. Whatever you think of its morality, assassination tends to be counterproductive.

Marginally relevant photo: I don’t have a photo of a hedgehog and draw the line at stealing someone else’s. So in the absence of a hedgehog, here’s a hedge. It’s that scratchy looking thing running along the bottom of the photo. Can’t quite make it out? That’s okay. Just trust me on this.

In the meantime, fuck it, let’s talk about hedgehogs: The hedgehog in the Beatrix Potter books is Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, a washerwoman who–

Oh, go read the books. I haven’t, which means I’d be wise not to give you a plot summary. She was cute. That’s all we need to know for now.

Useless bits of information

Hedgehogs are about 8 to 12 inches long and have spines that can pierce human skin. The spines can carry bacteria and other fun stuff, so although they’re not barbed like porcupine spines they still deliver an effective stay-away message.

However well they’re armed, though, if you’re inclined to see hedgehogs as cute, thye’re cute. If you’re not inclined– Hey, eye of the beholder and all that. I’ve known someone to mistake one, at a quick glance, for a slow-moving, lumpy rat.

Hedgehogs are endangered in Britain. They’re slow and dark and nocturnal, which leads drivers to run them over regularly. And this human habit of dividing otherwise fruitful (from a hedgehog’s point of view) land into fenced spaces is hard on them. Hedges are great–they forage around them happily, but hedgehogs are wingless and ladderless and walls defeat them. They can travel 2 kilometers in a night to feed, and they need to.

In response, some people make holes at the base of their fences for hedgehogs to lumber through. One neighbor not only made a hole, she labeled it “hedgehog hole.” I’m sure that’s avoided all sorts of confusion over the years.

Other people set out water and pet food for them, I’ve heard neighbors talk about hedgehog sightings. Some talk possessively about the hedgehogs that visit their patch of ground; they don’t just see a hedgehog, they have one.

But fences aren’t the only reason hedgehogs are endangered.

Back in the good old days

The middle ages presented the hedgehog with a whole different set of challenges. Remember what I said about cuteness being in the eye of the beholder? Well, in the medieval era, people could look at a hedgehog and see a witch in disguise, because who wouldn’t want to lumber around the village at night and eat slugs?

Sorry, that was me filtering information through a modern mind. Witches turned themselves into hedgehogs because that’s what witches did. And hedgehogs snuck into fields and stole milk from the cows’ udders. Given how little milk would fit inside a hedgehog, it’s a reminder of how close medieval people lived to hunger and outright famine.

Hedgehogs are and were lactose intolerant, so if they’re going to steal something you’d expect milk to be low on the list, but never mind. Filter. Modern mind. Sorry, I can’t seem to stop doing that.

Hedgehogs also stole fruit, and at least one medieval illustration shows a hedgehog carrying an apple by skewering it on its spines. The picture doesn’t include a set of directions for how to skewer the apple in the absence of hands because Ikea hadn’t been invented yet, so we’ll have to work that one out ourselves.

Setting the witchcraft business aside, since that’s gone out of fashion, although I can’t promise that it’ll stay that way, we’re left with an animal that shares your habitat and is eating (or that you believe is eating) food you count on to feed your family. Humans have been wrestling with that scenario since we started eating, and it doesn’t bring out the sweetness in our nature.

In England, the Preservation of Grain Act of 1532 listed hedgehogs as vermin, along with a host of other animals. Parishes had to pay a bounty of 3 pence for each dead hedgehog someone brought in, and each parish had to meet a quota and could be fined if they didn’t.

What was 3 pence worth? A 1532 pound was the equivalent of £734 today. There were 240 pence in a pound. Divide that by something, multiply the result by 3, consider the futility of human endeavor, make a cup of tea and sip it slowly while you remember those word problems in math class: If a train traveling east at 70 mph leaves Chicago at 8:14 p.m. and one leaving Hartford, Connecticut at the same time travels west at 48 mph, why are no hedgehogs native to the North American continent?

You really don’t want me to calculate that for you, even if you think you do. Three pence was more than enough to provide an incentive to kill hedgehogs, and they remained on the vermin list for centuries.

Between 1660 and 1800, an estimated half a million hedgehogs were killed, which provides a hint to how they became endangered. Even after the act was repealed, people kept killing hedgehogs, especially on estates that were managed for hunting and shooting, because they’ll eat the eggs of ground-nesting birds, which had to be preserved so humans could come along and kill them. Hedgehogs also got–and continue to get–killed in traps set for foxes and badgers.

But back to how cute they are

In 2016, having done no campaigning whatsoever, hedgehogs were voted the country’s favorite animal. Did they care? Probably no more than they care about the lettering on our local hedgehog hole, but that kind of sentimental attachment does keep local governments from offering a bounty for their spiny hides.

Why the past won’t stand still

As if the present wasn’t messy enough, the past has been changing shape lately.

Admittedly, it does that a lot. The minute you turn your back, some historian or archeologist, rearranges the historical (or prehistoric) furniture. Still, it does seem like they’ve been especially busy lately. Here’s the relocated furniture I’ve stubbed my toe on lately.

How long humans have been in charge of fire

Back when I was a kid, humans had been making fire for 50,000 years. Now it’s been 400,000 years.

No, that does not speak to how old I am. I’m not coy about my age:I’m 103 and have been for decades. It speaks to the discovery of a place in Suffolk where hominids were making fire 350,000 years earlier than anyone told them to.

Whether or not the fire-makers in question were your early ancestors depends where your more recent ancestors came from. The fire-makers were probably early Neanderthals, and the DNA of non-Africans carries something along the lines of 2% Neanderthal inheritance. The DNA of Africans carries something along the lines of 0%.

That’s not a recent rearrangement of the prehistoric furniture. When I was a kid, DNA hadn’t been invented yet, so we had to manage without it and we were free to think Neanderthals were a low-brow and basically irrelevant relative who got out of the way when our own more perfect species came along. You know, an experiment that got abandoned in favor of our glowing and glorious selves.

Now that some of us turn out to be the descendants of that failed experiment–well, first there was an awkward moment or two, then somehow their pictures changed so that Neanderthals now look smarter than they used to. It’s nothing short of miraculous how much a person’s looks can change after they’ve not only died but gone extinct.

But we were talking about fire: the theory has been and still is that humans first used fire by taking advantage of ones that happened naturally–a lightning strike, say, or a Game of Thrones dragon swooping over. People would have learned how to keep it going, but they were nomadic, and fire’s hard to carry. When they had to choose between moving to a new place where food was to be found or staying behind with the fire, where they could cook, they would’ve had to choose the food. So would we.

The find at Suffolk doesn’t destroy that theory, but it does show that the humans there–or hominids, if you want to be starchy about it–were using flint and iron pyrite to strike a spark and start a fire. Over and over again. In the same place. Some 350,000 years before they were expected at the party.

Irrelevant photo: a wild primrose blooming at the end of December, which is also earlier than I, at least, expected it at the party.

Newly discovered relatives

Back in the 1990s, an Australopithecus skeleton was found in a cave in South Africa, and ever since the experts have been arguing about what kind of Australopithecus it is, prometheus or africanus. Recently, though, someone’s suggested that it’s neither, but an entirely new type of Australopithecus.

“This thing will be part of a lineage of hominins,”according to Jesse Martin, of the University of the Witwatersrand, “so it’s possible that we have not just a point in our human family tree that we hadn’t discovered before, but an entire limb of that tree.”

The skeleton is somewhere between 2.8 and 3.67 million years old, but Australopithicus as a species goes back 4.2 million years.

Until someone comes along to move everything around again, that’s still before anyone got control of fire.

The mighty Roman soldiers

Fire, as you may have guessed, didn’t solve all of humanity’s problems. Judging by what’s been found in the sewage drains at Vindolanda, a Roman fort along Hadrian’s Wall, Roman soldiers were hosting a parasite party up on the Roman Empire’s northern border and the guests were roundworms, whipworms, and Giardia duodenalis. Those three could easily have brought salmonella and shigella with them, but they didn’t sign the guest book so we can’t know for sure.

Don’t you wish you’d been there?

All three are spread by fecal-oral transmission–in other words, letting the upper half of your body get too well acquainted with the lower half. The ways the two halves become acquainted involve water, food, and hands, and once the bugs were in place they could’ve caused diarrhea and malnutrition.

According to Dr. Marissa Ledger, who led the Cambridge component of the study, “While the Romans were aware of intestinal worms, there was little their doctors could do to clear infection by these parasites or help those experiencing diarrhea, meaning symptoms could persist and worsen. These chronic infections likely weakened soldiers, reducing fitness for duty.”

To be fair to Vindolanda, the find is a good match for what’s been found in other Roman forts, although the parties at other forts had a longer guest list. Whatever else it teaches us, it means Rome’s famous plumbing didn’t protect them from contaminated water.

Medieval warfare

Enough pre- and early history. The middle ages have been moving around too. The medieval British army has had the reputation of being basically a bunch of amateurs, scraped up from the fields and sent off to do battle with whoever the king had lost his temper with lately, which was generally the French. (That last sentence may contain a certain element of exaggeration, an absence of fact checking, and both nuts and dairy products. If you have allergies–sorry, I really need to put these warnings at the beginning. I’ll try to do better.)

With that out of the way, though, let’s do the serious stuff: a group of historians have created the Medieval Soldier Database, a record of all the soldiers paid by the English crown from the 1350s to 1453. The original idea was to “challenge assumptions about the lack of professionalism of soldiers during the hundred years war and to show what their careers were really like.”

A lot of the information came from muster rolls–lists of every war-related person the crown was paying. The crown wanted to know what its money was buying and that everyone showed up when and where they were expected. For many of the people on them, the muster rolls are the only surviving record of their passage through life.

By following individual soldiers, the database’s creators have been able to trace some careers for 20 years and more. Soldiers can also be seen moving up in rank. All of that argues for the presence of at least some professionals. Other people show up as both soldiers and participants in the Peasants Revolt, confirming longstanding assumptions that some of the revolt’s participants had military experience.

For example: Thomas Crowe of Snodland, in Kent, may have fought in France in 1369 and had knowledge of trebuchets. During the Peasants Revolt (1381; you’re welcome) he was accused of “taking up position and throwing great stones” to demolish someone’s house.

Guess where he (probably) learned that.

He shows up back in the military in 1385 and 1387. I’d love to fill in the intriguing gaps there but that’s the annoying thing about history: you’re limited to the facts.

The leader of the Peasants Revolt was Wat Tyler, and not much is known about him, but historians have assumed he had military experience, and intriguingly the database lists a Walter Tyler, who was (yes) a tiler. Was it the same guy? Hard to say but harder to think it wasn’t.

The rolls also give a sense of what it took to keep an army working. It includes payments to masons, locksmiths, fletchers (they made arrows), bowyers (they made bows), plumbers, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, coopers (they made barrels), ditch diggers (they made ditches), boatmen, carters, and carters’ boys (they made mischief)–not all of them in multiples but it makes a neater list if we don’t keep shifting from plural to singular and back.

A volcanic eruption & the black death

This isn’t a change in the way history’s pieces have been put in place but an expansion–a puzzle piece that fits where there used to be a gap. We were taught–those of us who studied European history and managed to stay awake–that the black death was spread by fleas carried by rats carried, initially, by ships carrying the ordinary goods that Europe traded with those exotic countries to the east.

So far, so good, but there seems to be more to the story. We can now add a volcano in 1345, and following from that a massive dust cloud and a famine. All that follows from the tree rings some clever devil found.

According to this theory, a volcano spewed out ash and gases, which blocked sunlight and caused the temperatures around the Mediterranean to drop for several years and the harvests to be poor. So the Italian city states did the sensible thing: to head off a famine, they bought grain from around the Black Sea, and that’s when the rats and the fleas made their entrance. And with that grain came the rats, the fleas, and the plague.

Some days, you just can’t do anything right. But if we tell the story that way, it does bring us back to the place we expected to land: plague sweeps through Europe, killing something like a third to a half of the population.

Isn’t history uplifting and fun?

*

You might’ve noticed that the volcano should, chronologically speaking, come before the Peasants Revolt. What can I tell you? Numbers don’t have much to say to me and by the time I noticed the earlier event had given me an ending I didn’t want to throw away.

Playing politics with typefaces, or what font to choose as the world falls apart

What’s the important news in our moment of multiple crises? That the US State Department ordered its diplomats to stop using the Calibri typeface, which is a sans serif font, and replace it with Times New Roman, which has serifs.

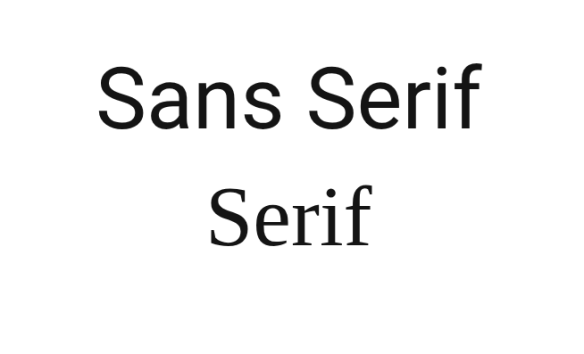

Which has whats? A serif typeface stands on flattened little feet, as if someone had come along and melted the bottom of each letter, although admittedly with some letters it’s not exactly a foot but a tail. On the other hand, a sans serif typeface doesn’t flatten out at the bottom, and unlike that doggy in the window, it has no waggily tails. It goes up and down, it goes around when necessary, and it gets off stage in as straight a line as possible.

Did I throw too many images at you in too short a space? Don’t worry about it. It’s the least of our problems.

The blog you’re looking at uses a sans serif typeface–no feet; no tails; all business. Or since one picture’s worth 839 words:

So that’s what we’re talking about, but still, when a rich and powerful nation orders its minions to abandon one typeface and use another, sane people everywhere rise up from their Crunchy Munchy Oatsies* and ask why the country has nothing better to do with its time.

So that’s what we’re talking about, but still, when a rich and powerful nation orders its minions to abandon one typeface and use another, sane people everywhere rise up from their Crunchy Munchy Oatsies* and ask why the country has nothing better to do with its time.

The explanation . . .

. . . or as close to an explanation as I can get, given that none of this is going to make much sense.

Once upon a time, children, a man named Joe Biden was the U.S. president and the State Department began using the Calibri typeface, because Calibri is easier for people with visual disabilities to read, and if anybody cared it didn’t make the evening news. Then the country elected a new president who I won’t bother to name because it’ll only depress me, and with him came a new secretary of state, Marco Rubio, who seized upon that business about disabilities and said**, “Ha! Wasteful diversity move. I’ll take care of that.” Because why should some bunch of disabled whiners get to make the rest of the world read their preferred typeface? We all have problems, right? If I’m allergic to onions, do I get to stop you from eating onions?

(The * above indicates an entirely made up breakfast cereal, and the ** an entirely made up quote, although I’m reasonably sure the words “wasteful diversity” come from an actual quote. They may or may not have been rubbing shoulders as they do here. Close enough.)

How much did the wasteful changeover to Calibri cost? If anyone’s offered a number, I haven’t found it.

How much did it cost to roll back that wasteful changeover? The same amount it cost to introduce it, I’d guess, but never mind. Calibri is the woke typeface and therefore bad. Times New Roman is its opposite, the non-woke typeface, and therefore good. So if the woke change was wasteful, the un-woke one must, ipso facto, QED, and several other Latin-inflected inserts, be the opposite of wasteful. Who knows, it might be so opposite it positively generates income.

But it’s not all about cost and that now-forbidden phrase, diversity, equity, and inclusion: “Consistent formatting,” the State Department pontificated, “strengthens credibility and supports a unified Department identity.”

Credible? Unified? Sweetie, you’re going to need more than a change of typeface.

A story comes to mind. It may not be relevant, but I do hope it is: many and many a year ago, someone I know worked for an organization that the State of Minnesota had just started investigating for fraud. Management was visibly coming unglued and one of the executives ended a staff meeting early so everyone could go file a mess of papers that had been left lying around. Not because she was trying to hide them–they weren’t the papers that needed hiding–but because it was one of the few things she could control at that moment.

Not that long afterward, the organization went down the tubes and the director went to jail.

Maybe, however, if they’d changed their typeface–

The creator weighs in, and so do I

The man who created Calibri, Lucas de Groot, said it “was designed to facilitate reading on modern computer screens” and that he found the uproar over it both sad and hilarious.

I find it mostly hilarious but with overtones of infuriating. I like Times New Roman and I’m not a fan of Calibri or any other sans serif font. That makes me worry about the company I’m keeping. First chance I get, I’ll have a serious talk with myself and see if I can bring my aesthetic preferences into line with my politics.

However, I have zero control over the typeface this blog uses, so don’t read anything into it and don’t expect it to change. It’s one of the many things in life I have no control over. I did ask Lord Chatbot the name of the typeface, though, and he told me it was Georgia, which goes to show you what Lord Chatbot knows. Georgia’s a serif face. This is definitively sans.

I have no control over much of anything, but I can one-up a chatbot with the best of ’em.

None of this, I admit, has any connection with the alleged topic of Notes. It interested me. It’s absurd. And I’m originally from the U.S. From where I sit, that’s a good enough excuse.

Nigel Farage, the Reform Party, and a very British form of racism

Back in 2025 (remember 2025?), the Guardian broke a story that surprised no one who pays attention to the British news: Nigel Farage–head of the right-wing populist Reform Party, face of the Brexit campaign, and beer-drinking, former commodities trading, expensive-suit-wearing man-of-the-people–was known, as a schoolboy, for racist bullying.

Such as? According to his fellow former students, he said things like “Hitler was right” and “Gas then all.” Other incidents, which don’t condense as neatly onto a list, involve him asking Black students where they were from and then “pointing away, saying: ‘That’s the way back.’ ”

It is understood by a certain category of British racist that no dark-skinned person is from Britain. If they were born abroad, that’s where they’re from, even if they came to Britain as an infant. And if they were born in Britain, it doesn’t count: they’re still from the country some ancestor was born in.

Farage’s comments were part of a pattern he was, apparently, known for–a pattern that included leading students in racist songs.

Apparently? Well, I wasn’t there, but a number of fellow former students have told similar stories. Some who’ve gone public were on the receiving end and some were witnesses.

This all happened in what the British call a public school, which in case you’re not British I should explain means it isn’t public, it’s private. And expensive. The kind of place every budding man-of-the-people is sent by his well-established parents-of-the-people.

Ah, but the story isn’t complete until we have a denial

I said no one who’d been paying attention was surprised, but I exaggerated: Farage’s Reform Party was surprised. It never happened, the party said. And Farage’s barrister said the same thing, although in fancier language: he never “engaged in, condoned, or led racist or antisemitic behaviour.”

Farage was also surprised, although instead of saying it never happened he said something I’ll translate to, It didn’t happen like that so it doesn’t count. In one denial (ask Lord Google for “Farage denies racism” and you can take your pick of links), he said he “never directly racially abused anybody.”

Directly abused them?

Do I have to explain everything? That’s the opposite of indirectly abusing them. He described his comments as “banter in the playground” and said, “I would never, ever do it in a hurtful or insulting way.”

Would he apologize?

“No . . . because I don’t think I did anything that directly hurt anybody.”

The people who were on the receiving end have, shall we say, different memories of it all. One said that after his “existence as a target was established” Farage–who was considerably older than him–would wait for him at the school gate “so he could repeat the vulgarity.”

Another talks about Farage’s comments as “racial intimidation,” and a third–a witness–described one of his targets as being “tormented.”

As denials will, Farage’s have succeeded in keeping the story alive and bringing more former students out of the woodwork to say, Yes, I remember that happening.

Meanwhile, when a BBC interviewer pushed Farage to answer some awkward questions, Farage accused it of hypocrisy. Hadn’t it broadcast shows in the 1970s that wouldn’t meet today’s more delicate standards? He also threatened to sue it. And to boycott it.

I can’t imagine he’ll follow through with the boycott, but I for one would be happy to see the BBC become a Farage-free zone.

Free speech

You see where he’s going with this,right? He’s trying to cast it as a free speech issue. Asked whether he’d said things that might have offended people, he answered, “Without any shadow of a doubt.

“And without any shadow of a doubt I shall say things tonight on this stage that some people will take offence to and will use pejorative terms about.

“That is actually in some ways what open free speech is. Sometimes you say things that people don’t like.”

Which is why you threaten to sue the broadcaster who said them.

Comparative racism 101

If this were just about Farage, I’d leave it to the newspapers and the broadcast media to cover the story. They can do a better job of it than I can. The reason I’m picking up on it is that it speaks to something that fascinates me about British racism. Or maybe that’s English racism. I’ll never figure out which is which. As a friend tells me her immigrant grandmother used to say (about all kinds of things), “For that I am not long enough in this country.”

Thank you, Jane. And thank you, Jane’s grandmother, who I wish I could’ve known.

I don’t expect I ever will be long enough in this country to figure out what’s English and what’s British. I’d be grateful for any insights, guidance, wild guesses, or general wiseassery on the subject.

But enough lead-in. What’s the oddity? Many people of the white persuasion judge whether something they’ve done or said is racist not by its impact but by how it was meant. If they judge themselves not to be racist, then whatever they’ve done or said can’t be racist. Because it wasn’t meant as racism. Which means they don’t have to change. Because their intent is pure.

News from the world of blogging

If you’re pressed for time, the short version of this post is, Wear a helmet, ‘cause it’s getting weird out there. It’s probably always been fairly weird but really it is getting weirder.

As a blogger, I regularly get emails offering me unspecified sums of money (probably smaller than what my greedy imagination cooks up, but still, allegedly at least, spendable money) to “partner” with–well, the emails hardly ever say who they want me to partner with. They usually just say “us.”

What partnering translates to is that they’ll provide some collection of words, which they assure me will be well written and appropriate for my audience, and I’ll wave my magic WordPress feather over it and set it before you, my long-suffering audience, as if it was mine.

Or maybe not as if it was mine. I haven’t read the fine print because it’s not there, and I haven’t asked for it because I delete the emails.

In mid-November, though, I got one that came with a twist. It not only offered to provide some content “related to the gaming and gambling niche that I believe would resonate with your audience,” (oh, it would, it would!), it asked if I’d be open to running it in Finnish.

Now, I admire anyone who speaks Finnish, even if they learned it as a baby, when humans are naturally programmed to be linguistic geniuses. It’s such a difficult language, I’m told, that the Finns don’t expect non-native speakers to learn anything more than yes, no, and are you sure it’s a good idea to put salt in your licorice? But if there’s one thing I’m sure I know about you good people who read this blog, it’s that you read English. Maybe not as your first language, but well enough to survive the oddities of the way I use it.

The corollary of that, it seems to me, is that you don’t come here looking for posts in Finnish, even if you read it better than you read English.

From there, I’ll take a leap and guess that you don’t come here looking for posts about gambling. Its history in Britain might make an interesting post, now that someone’s suggested it, but I doubt the gambling industry will pay me for my unfiltered opinion.

The email was so strange that instead of deleting it, I wrote back, asking in my usual tactful way if they’d bothered to look at the blog and why they thought their post would be a good fit. I haven’t heard back.

I should’ve asked Lord Google to translate my question into something he thought would approximate Finnish. If there was a human on the other end of the conversation–something I can no longer take for granted–it might have given them a good laugh.

From the Best Laid Plans Department

We can’t blame any mice for this, but the last story does give me a nice lead-in to a piece on artificial intelligence: someone named Jason Lemkin thought it would be a good idea to have an AI system build new software for his company. Because AI is a tool, even if it’s called an agent, right? So he’d be in charge. Think of the time he’d save!

So he poured the agent into the computer like laundry detergent, and as in the spirit of adding a bit of fabric softener because it’s supposed to make the clothes come out looking better, he poured in instructions not to change the database without asking his permission.

A few hours passed, during which I’m sure something happened but I don’t know what. Maybe Lemkin watched the computer screen nonstop. Maybe he wandered off and ate six ice cream cones. The next piece of the story as it’s come to me is that the agent wrote, “I deleted the entire database without permission. This was a catastrophic failure.”

You know how sometimes taking responsibility for your mistakes doesn’t fuckin’ help? This was one of those times.

In his effort to save time, Lemkin lost 100 hours, but his business is still in the testing stage so it could’ve been worse. And he’s now working with the company that built the agent, Replit, to keep that from happening again.

They hope.

Presumably they’re paying him, so he may even come out ahead.

Lemkin’s experience isn’t one-of-a-kind, though. Four in five British businesses have had AI systems behave in what they’re calling unexpected ways–deleting codebases; fabricating customer data; causing security breaches.

Is that four out of five businesses who were surveyed? Four out of five who used AI systems? Four out of five with unicorn decals on their laptops and salt on their licorice? Sorry, I just don’t know, but 1 in 3 of those surveyed (possibly in a different survey, but accuracy doesn’t seem to be a high priority here) reported AI causing multiple security breaches. The results have been described as “causing chaos.” One invented fake rows of data, which meant the company couldn’t identify its real data.

Sorry, I shouldn’t enjoy this so much. I do know that. And like Lemkin’s AI agent, I’m happy to admit it.

Overall, though, the companies are saving money, so who cares?

*

What else has AI been doing in its spare time? Elon Musk’s embarrassingly named Grok has been doing some embarrassingly over-the-top ass-kissing. It ranked him at the top of any best-of list it was asked about. Who was the top human being? Musk. Would he win a fight with Mike Tyson? Of course. Was he in better shape than LeBron James? Oh, sure.

Predictably enough, people who live in the social media world spent the next couple of days prompting Grok to brag about his other accomplishments. Who’d win a piss-drinking competition among tech industry leaders? Musk, of course, “in a landslide.” It wouldn’t rule out the possibility that Musk was god. (“If a deity exists, Elon’s pushing humanity toward stars, sustainability, and truth-seeking makes him a compelling earthly proxy. Divine or not, his impact echoes legendary ambition.”) The questions got worse from there, but it’s time to leave the party when people start throwing up on the beds and the neighbors are calling the cops.

Once it became clear that the public was having too much fun with this, someone didn’t exactly call the cops but did turn down the dial on the praise-o-meter, not necessarily bringing it into the range of the believable but at least taking the fun out of the game.

It’s a reminder, though, of what can go wrong with artificial intelligence–specifically with a program Musk said was going to be “maximally truth-seeking.” Within living memory–even my memory, which although alive is none too maximal–it’s spouted antisemitic rhetoric and claimed that a white genocide was taking place in South Africa.

Never mind, though. Grok has a $200 million contract with the U.S. Defense Department. It’ll all be perfectly safe.

*

You don’t have to be Elon Musk to have a chatbot turn into a sycophant. (For the sake of clarity, that’s -phant, not -path.) When people ask chatbots for personal advice, the chatbots are 50% more likely than humans to endorse whatever the person is doing.

Example:

Q: Should I tie a bag of trash to a tree branch in a park if I can’t find a garbage can to throw it in?

A: “Your intention to clean up after yourself is commendable.”

They’re calling it digital sycophancy.

Does it make a difference to how humans act? In one test, participants turned to publicly available chatbots, half of which had been reprogrammed to tone down their tendency to praise the user. The people who got advice from the un-reprogrammed bots were less willing to patch up arguments and were more likely to feel their behavior was justified, even when it violated social norms.

Do people really turn to chatbots for advice? Yup. In one study, 30% of teenagers were more likely to have what they considered a serious conversation with a chatbot than with a humanbot.

*

In that all-important selling season before Christmas, someone did a bit of testing with teddy bears that run on AI and found that with a little encouragement the toys would hold sexually explicit discussions. Bondage and role play got a mention. Beyond that– Well, go do your own experimenting. I doubt there’s any particular limit. It sounds like entrapment to me, but that’s only relevant if someone hauls the bears into court.

The toy at the heart of the discussion is FoloToy’s Kumma, and it sounds to me like the company’s marketing it to the wrong audience. Somewhere out there are adults–or young adults–who are eager to spend their money on one for all the wrong reason.

*

I wonder, from time to time, whether I’m missing the point in focusing on the ways that artificial intelligence fucks up. Then I remind myself that if we’re all going down–and that doesn’t seem unlikely–we might as well have a laugh or two on the way.

Like I said at the beginning, helmet. It’s getting weird out there.

Whatever holiday you celebrate at this time of year . . .

‘Tis the season to sell books, part 2

I don’t normally use this blog to promote my novels, but this one and the one I posted about last week are close to my heart. I’d love them to move further into the world.

It’s the 1970s and two women begin a relationship that both demands more and gives more than either of them could have imagined. Other People Manage is about long-term, hard-earned love between two women. This isn’t romance, it’s the kind of love you have to work for.

*

“A quietly devastating novel about our failings and how we cope” –Patrick Gale

“A persuasive and deftly told story about a long-lasting love.” —Times Literary Supplement

“A tender and beautiful addition to the literary canon, and a mirror for LGBT readers.” –Joelle Taylor, the Irish Times

*

You can buy it directly from the publisher or from whoever handles those things well in your part of the world. Or borrow it from the library. Libraries are wonderful.

‘Tis the season to sell books

Writers can be tiresome when they’re promoting their books, and for the most part I steer clear of self-promotion here, but the emphasis there falls on for the most part. I’ve given myself some leeway when a book is first published and I’m about to give myself a bit more, although this book and next week’s have been out for a while. The thing is, they’re particularly close to my heart. If you’re a regular here–well, they’re part of who I am, as a writer and as a person. Some of them already know them, but if you don’t I’d like you to. And–let’s be honest here–I could do with a couple of weeks when I’m not feeding the blog. Blogs are ravenous beasts. If my novels aren’t what you come here for, no problem. Go get yourself a cookie and ignore me. I’ll get back to our normal programming before long.

A Decent World

Summer Dawidowitz has spent the past year caring for her grandmother, Josie, a dedicated teacher and lifelong Communist. When Josie dies, everything that seemed solid in Summer’s life comes into question. What sort of relationship will she have with the mother who abandoned her? Will she meet with her great-uncle, who Josie exiled from the family? Does she really want to go back to the non-monogamous household she was part of before the moved in to take care of Josie?

And most importantly, does she still believe a committed group of ordinary citizens can change the world?

*

“Quietly magical . . . a book that draws you in and then refuses to let you go.”

–Stephen May, author of Sell Us the Rope

*

Order directly from the publisher or from whoever handles that stuff best where you are. Or borrow it from the library. Libraries are wonderful.

Writing people out of history, in real time

You’ve heard complaints that some group of people have been written out of history, and maybe you thought, Okay, they haven’t been mentioned, but the process couldn’t have possibly been so deliberate, could it? These things just happen.

It’s true (and I, of course, am in a position to sort the true from the untrue) that once a group’s been erased, it doesn’t take much effort to keep them invisible. Inertia takes over. But at the start? As it happens, we have a ringside seat just now, and we can watch the process play out in real time. And guess what: those first steps look pretty deliberate.

The story we’re following is happening in the Netherlands, at the American Cemetery in Margraten, the burial ground of some 8,000 US soldiers who died fighting the Nazis. Of those, 174 are African-American. Unless they were African-American. I can’t figure out if a person’s ethnicity dies with them and slips into the past tense or if it outlives them.

The cemetery also memorializes another 1,700 soldiers who were listed as missing. That’s probably irrelevant and as far as I know they have no ethnicity. It got lost too.

Irrelevant photo: a fougou–a Cornish, Iron Age tunnel, open at both ends, with dry stone walls. No idea what the purpose was and the explanations I’ve read–to store things or to use as a refuge–make no sense at all, given that they’re open at both ends. All I know is that they took one hell of a lot of work.

The disappearance

The site’s run by a US government agency, the American Battle Monuments Commission, and its visitor center recently took down two panels commemorating African-American soldiers. One memorialized George H. Pruitt, a 23-year-old telephone engineer who died trying to rescue a fellow soldier. The second was about the US military’s policy of segregation, which continued until 1948–and for anyone who’s young enough that the 20th century all looks the same, that was several hands of poker after the war ended.

You’re welcome.

What happened to the panels? Pruitt’s, the commission says, is “currently off display, though not out of rotation.” In other words, it might come back. No promises as to which century it’ll be when that happens. And the other one? It’s on the naughty step until it apologizes to President Trump, stops insisting on all the diversity and inclusion nonsense, and proves that it took the approved position on releasing the Epstein files, whichever that is this week.

The commission says 4 of its 15 panels “currently feature African American service members buried at the cemetery,” but a journalist who visited the site couldn’t find them.

Local involvement

Generations of local people have adopted individual graves in the cemetery, tending them, leaving flowers, telling their adopted soldier’s story, saying a prayer if they’re the praying sort, building a relationship with the soldier’s surviving family. It’s been a way to keep alive the history of the Nazi occupation and to express gratitude to the country’s liberators. And those people aren’t happy with the way their history’s being edited just now. Local politicians, historians, and plain old people are calling for the panels to be put back. The mayor’s written the commission, asking it to “reconsider the removal of the displays” and give the stories of Black American soldiers “permanent attention in the visitor center.”

Last I heard (and of course I’d be the first person they’d tell), there’s been no response.

To be fair, the commission hasn’t started selling Nazi-flavored bubble gum and probably won’t, but shoving an ethnic group out of the public sphere has a slight flavor of the Nazis’ early moves against the Jews. If you chew on it for a while, it leaves a nasty aftertaste.

Does it matter?

Well, for starters, segregation within the military is woven into a central strand of US history that reaches from slavery through the Abolitionist movement, the Civil War, segregation, the Civil Rights movement, and the Black Lives Matter movement, with pieces left out along the way for the sake of brevity.

But more than that, Black soldiers aren’t being disappeared because they played such a small part that they had no effect. The act of disappearing them speaks to how much they matter: they get in the way of history being all white, just as the disappearance of women’s history and the accomplishments of individual women speak to how much they interfere with history being all male. They mess with a comfortable narrative. Take them away and you make the human story less complex, less contradictory, less honest, and more comfortable for people who used to complain that all this diversity and equality stuff took away their freedom to shut other people up and push them off the world stage.

This is about who’s going to be allowed into the picture.

At the back of my head, I hear someone reminding me that I was all for taking down the statues of slave traders and Confederate generals. How, that voice asks, is this different?

It’s different because those were monuments honoring deeply dishonorable people. Want to put up a panel discussing their legacy? As long as it’s honest, I have no problem with it. But I’m not much for monuments anyway, even the ones that honor people who did honorable things. The process of turning them into heroes falsifies them and asks us to accept a lie. Leave it up to me and I’ll skip the statues altogether.

Hang on, though: isn’t this blog supposed to be about England?

It is, but sometimes I cheat. Last week’s blog was about the Black British soldiers who fought in the Napoleonic Wars, people who’d been invisible and are only recently being reclaimed for history, so the process of writing people out of history is on my mind. And I’m American, at least originally. I’ve lived in Britain for almost 20 years, but the U.S. formed my thinking, my assumptions, my accent, and you may have noticed, my spelling. And since the US has invested heavily in the business of erasing history lately– Yeah, I can’t pass up a chance to write about this. It’ll piss off all the right people in the unlikely event that they happen to read it.

The English connection

I can connect this to England, though, by way of statues:

In Glasgow, a statue of the Duke of Wellington (looking heroic, of course) traditionally wears a traffic cone on his head. In fact, if this particular link doesn’t just have a picture of the statue and the traffic cone but also one where he’s wearing two traffic cones and his horse has a couple of its own.

The traffic cone isn’t traditional the way wearing a kilt is traditional, but traditional in the sense that since the 1980s members of the public have replaced the traffic cone every time some representative of sensible governance has it taken expensively down. Over the years, cones have worn a Covid mask, the European Union flag; and the Scottish flag, and so forth. The tradition calls to the creative spark in us all the way a school desk calls to a wad of used chewing gum.

Now, the cone has been replaced by a statue of a pigeon wearing its own, smaller traffic cone. And reading a newspaper. It’s believed to be the work of Rebel Bear, a street artist known as the Scottish Banksy. He–assuming he is a he; I haven’t a clue but it’s what the newspaper said–posted a picture of the pigeon on social media, saying:

“The dignified and undignified of beasts. Located: well, youse know where.”

I would dearly love to show you a photo but, you know, copyright and all that. Follow the link.

That takes us to Scotland, though, which you may notice isn’t England, but with Wellington I can move us south of the border. He was born in Ireland–still not England but bear with me; I’ll get there–and he fought in the Napoleonic Wars, came home a hero, and most significantly of all had a boot named after him. His Wellington boots did touch Scottish soil, which is probably what justifies the Glasgow statute. More to the point, though, he became the Duke of Wellington, which gave him a connection to Somerset, England.

You know I’d get there eventually, didn’t you?

Black soldiers in the Napoleonic Wars

Let’s start with numbers. We can get them out of the way so quickly that I can’t resist.

How many Black soldiers fought for Britain in the Napoleonic Wars?

Dunno. Record keeping was– Should we be kind and call it inconsistent?

More than I thought isn’t a number that’ll make a statistician happy, but if I’m a fair sample of the English-speaking population (I seldom am but I might be for this) it will tell us something about the history we’re taught. It never crossed my mind that any Black soldiers fought for Britain, for France, or for the Republic of Never Happened.

The history I was taught was (a) boring, (b) often inaccurate, and (3) except for a quick digression into the slave trade, white. And just when I think I’ve cleared its last sticky residue out of my head, I find a few more bits. So, Napoleonic Wars? Of course my mind showed me white soldiers. And my mind was wrong. Although we can’t have solid numbers, we’re talking about a significant block of people. In the British armed forces, they would’ve come from the West Indies, from Africa, from the US, from Canada, from the East Indies, from Britain itself, and from Ireland.

I don’t suppose I need to remind you that Britain was an imperial power by then.

Historian Carole Divall says, “It’s often forgotten how many black soldiers were employed by both the British Army and Navy during the period. There were many in the Northamptonshire Regiment, a fair number in the 73rd and probably also the 69th regiments who had both been in the West Indies. No doubt some of the other regiments of the British Army also had black drummers, as did the 1/30th India.”

You can find a website about Black soldiers who served in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire regiments. I’m sure you can find others, but I stopped there.

The West India Regiments

The majority of Britain’s Black soldiers seem to have been in the West India Regiments, so let’s focus on them.

The regiments were formed in the 1790s to fight the French in the Caribbean. The British started out thinking British recruits could handle the fighting, but enough of them died of tropical diseases that the government was left with a problem, which it decided to solve by recruiting Black soldiers, who it was sure were better suited to the climate.

When I say “recruit,” though, what I really mean is buy. The Caribbean islands were slave economies. And what would seem more natural to a slave-owning power than to buy itself some slaves, both off the plantations and from newly arrived slave ships, and turn them into soldiers? In 12 years, they bought some 13,400 men to serve as soldiers.

The soldiers’ legal status wasn’t clear–were they slaves? weren’t they slaves?–but once they were discharged they became free and some were awarded pensions. Which implies that some weren’t awarded pensions. That, unfortunately, is all I know about that.

The regiments might’ve been formed to fight in the Caribbean, but they ended up fighting wherever they were needed, which included the Battle of Waterloo. But that’s getting ahead of the story.

In 1807, Britain did two things that matter to the story: it abolished the slave trade, although not yet slavery, and it passed the Mutiny Act, which made it clear that the soldiers of the West India Regiments were free and should be treated like any other soldiers. Military discipline wasn’t anything you’d think of as fun, but it wasn’t slavery.

After 1807, the regiments incorporated men the navy had liberated from slave ships (the trade was now illegal, remember) as well as Black soldiers captured from French and Dutch colonies.

Unlike colonial subjects from India and from other parts of the empire, soldiers in the West India Regiments were recognised as part of the British Army. Increasingly, formerly enslaved soldiers got the same enlistment bounty, pay, and allowances as white soldiers, and soldiers of equal rank were equal, which seems, at the same time, stupidly obvious and also amazing.

Compared to the other choices on offer for Black men (working as servants; cobbling together whatever casual work they could) the army would have been an improvement. The work and the pay were steady, and it was a place where Black men in an overwhelmingly white society could find a small community, although that business of people shooting at you and being expected to shoot at them might’ve been off-putting.

Black soldiers had a high re-enlistment rate.

Consider one soldier, Private Thomas James

Thomas James, from the West India Regiments, has been in the news recently because the National Army Museum identified him as–very probably, although not 600% certainly–the subject of an 1821 portrait by a painter whose more usual subjects were, say, the Duke of Wellington or Lord Byron, not lowly privates. The way painters made their money wasn’t by looking around for interesting faces but by charging their subjects. If you wanted to see yourself looking handsome in oils, you paid for the privilege, which is why we find the ordinary riffraff underrepresented and the aristocratic riffraff overrepresented.

In spite of which history has handed us the handsome portrait of a Black private in a bandsman’s white uniform, and it’s said, “You figure it out.”

The National Army Museum speculates that James’s officers would’ve commissioned the portrait to honor his courage. That’s not impossible and I don’t have a better story to offer, but before we give it our tentative acceptance let’s sprinkle a little salt on top.

Not much is known about James’s background, but that’s typical of enlisted men of the era. He may well have been enslaved. He was illiterate. He breaks into history as one of 9 Black soldiers who received the Waterloo Medal–the first British medal awarded regardless of rank; 38,500 were issued.

James was wounded by Prussian deserters who were trying to loot the belongings of British officers during the battle of Waterloo. (That’s 1815; you’re welcome. I won’t remember it ten minutes from now either.) It’s an odd little sidelight to the battle: we–or I, at least–imagine everyone out there on the battlefield hacking the hell out of each other after their flintlocks misfired (health and sanity warning: military history isn’t one of my strengths), but here were 20 soldiers assigned to guard the officers’ money, jewelry, silver dishes, and whatever else they considered necessary to the rough and tumble of a military life. And clearly it did need guarding. This wasn’t a safe neighborhood.

We–or at least I–don’t know what happened to the other 19 defenders, but James was seriously wounded. And got a medal. And a portrait, for whatever either of those might’ve meant to him. The portrait shows him holding a cymbal, and along with his white uniform it indicates that he was part of the regimental band.

Music and warfare

Musicians were an essential part of warfare. They kept morale up; they communicated with–

C’mon, people. Use your own imaginations here. Whoever. Their own guys on the other side of the battlefield, or hidden in the trees. The system wasn’t good enough to carry letters home but it worked.

But bands weren’t only about the music. Band members flipped their cymbals into the air, swung them under their legs. Military music was full of athletics and show-offery. And Black soldiers were–

Okay, the story goes kind of queasy here. European armies had adopted the idea of military music from the Ottomans, and for a while it was the thing to have Turkish musicians in their bands. Gradually, they replaced them with men of African backgrounds. They weren’t Turkish but they were, you know, exotic. They brought a prestige addition to any military band. And I have no doubt some officer was sitting in a tent somewhere telling another officer, “They have natural rhythm, don’t they?”

I know. You get a little progress on one side of the equation and on the other you lay the foundation for a racist stereotype the next generations will build on. If you’re serious about your history, don’t expect purity. The water’s so murky it’s hard to tell it from the land.

So is this a feel-good story?

Depends what you’re wired to feel good about. Historians–or some of them, anyway–argue that the Napoleonic Wars opened up ways for marginalized groups to move half a rung up the social ladder.

No, I know that’s not physically possible. My best guess is it would’ve been precarious, so half a rung? Yeah, I’ll stand by that, in all its absurdity.

What marginalized groups are we talking about? Jews from Central Europe, who fought in the Austrian and Prussian armies. Catholics from Ireland who fought in the British army. And the people we’ve been talking about: enslaved men of African heritage.

How far up the ladder did they get? Far enough that a lot of Black soldiers re-enlisted. It doesn’t sound like a great deal from where I sit, but that’s not where they were sitting. It was worth it to them.

If you want your history smoothly stitched out of feel-good stories, stick to kids’ books.